Building the Black Sound Archive

Black Sound is focused on celebrating and commemorating the impact of Black British music. As part of the Blakc Sound Exhibition, we invited visitors to bring in personal memorabilia that tells the untold stories of Black British music history. Whether it was a rare vinyl, cassette tapes, gig posters, instruments, clothing, or any item with a story to tell, our team used cutting-edge 3D scanning technology to digitally preserve these artifacts.

This process ensures that these important cultural pieces are not only celebrated today but also safeguarded for future generations. The digitized memorabilia will contribute to an ever-growing archive on Coventry Digital, making these hidden histories accessible to a wider audience and cementing their place in the legacy of Black British music.

The Archive

Bringing together crowdsourced artefacts, digitally preserved through 2D and 3D scanning technology, the Black Sound archive showcases the memories of the impact of Black British music on the Coventry community. The next phase will see this extended beyond Coventry to create a National archive of Black Sound. Members of the public were invited to bring in their artefacts and to recount their memories at a weekend event on 7 and 8 February 2025 at Coventry University’s Delia Derbyshire Building.

Where applicable, you can view the 3D models in full screen and interact with them in 3D.

Mackabee Sound International

Click play to listen to Daddy Sly and Mikey Magic talk about the importance of the Mackabee Sound system.

Audio Transcript

Hi I'm Daddy Sly from Maccabee Sound, and I'm here with my partner, Mikey Magic from Maccabee Sound. One of the reasons why we're here today is to bring what we believe is very important equipment to the reggae culture sound system. Maccabee is a sound system that started in 1981 to be exact, and obviously before then, we was building the sound system. So we brought a few items from even back in them days from the actual day one. We brought like preamp, power amps, and we brought some of our flags that we used to use, and banners and all that. So at the moment, that's what we feel [is] important. And people who don't know about the sound system business can actually learn from it. And because basically, these things are very old. I want to put you on to my partner, Mikey, and he's going to say a few words. Hello.

Hi, morning, yeah, as Sly said, we brought in a preamplifier, which is the original mixer from back in the day 1981 1980, a power amplifier, which is HH MOSFET and Beringer is another make as well that we've brought in, along with the Maccabee Studio International logo and the original flag from back in the day. So all of it is, in our opinion, well, it's our legacy for Maccabee Studio International and artifacts as well. So yeah, there's a lot of history here, and there's a lot of storytelling as well. So we can chronicle it from pretty much from day one as well. And there's obviously the original flyers, posters from back in the day as well, which we've carefully preserved. So yeah, that can all go in the archive as well. So, yeah, that's good, okay, thank you very much. That is from me, Daddy Sly and Mike Magic. Cheers. Thank you. Thank you.

Amos Anderson

Click play to listen to Amos Anderson’s talking about his amazing legacy, about setting up Glasshouse Productions and the training initiatives that were part of it.

Audio Transcript

When the Specials, when the Two Tone music got the mass with the record company, because I was involved with the record company from the early, at the time of the, you know, winding down, I spoke to the accountant of the Two Tone music, which is Ivor Cohen, to see whether there is a need, because at the time, black young, young black people, particularly from Coventry and in London as well, couldn't get a job. And these black young kids were leaving school being chucked out and stuff, so there was no home for them.

And I, I, we did a small feasibility studies where there is a need to actually develop a training to bring the young people away from getting into trouble, and particularly to give the young people a second chance, those that had been expelled from schools, because there's quite a lot of high turnover rate of our kids being expelled from schools. So yes, the little bit of feasibility study was showing that there is a need for education and to engage the local authority with the young people, to actually support to develop this training center, initially was meant to be so that's the thing.

Myself and my partner, Charley Anderson from the Selector, decided to set up Glasshouse Productions in Coventry. This is right after the demands of the tutor, and we called it Glasshouse Production so that record label which I set up , the music publishing, then you had a training company in those early days, music publishing, live entertainment agency within the industry, spectrum, spectrum. That was what was happening in Coventry. Okay, at that time, we set up because we said there's a need for education. We set up Glasshouse training. [] We first started as Glasshouse Training Limited, and then change the name to Access to Training and Enterprise, which is part of Glasshouse Productions. Does that make sense? Yeah, so the production thing is the commercial sector and the training division is the education. At that time there was nothing in the country, so that, therefore Coventry in the in the national to follow as a legacy of the Two Tone. Does that make sense? Here? You see where we see where that leading to. So to get this thing going, I have had to sort of do quite first of all, I've had to get the director of education within the local authority, Robert Aitken, have a meeting with him to, you know, explain the vision and the idea of it is to set up, what shall I say, a training to be funded, partly funded by the local authority, because it is in the hands of the local authority because of the use that's coming out. So I had this great meeting with the director of education, and yeah, Robert Aitken, and we had some of the member of the Selecter come and talk to Robert Aitken, Linda Goldwin, myself, Charlie Anderson, at that time, I've already set up this Glasshouse Productions in Coventry.

And so, what we were going to was saying that isn't good to have an education sort of situation to address this problem, and to have a Coventry School of faith. This is what this is. This was the whole issue here. The School of faith was supposed to be the fame thing. If you look through the Evening Telegraph, it's already recorded somewhere, and there's a right of it there. I couldn't even find it, but I will do later on to speak to what's his name there. Anyway, it turns out that I've had to sort of not only talk to the director of education from Coventry, we, in order to sell this concept with the education, we got this ... with the Glasshouse end of term. So you can see what is happening here. All the schools in the city, alright, all the school in the city were, were to sell this concept to the education, Director of Education, so that to get the old school involved. So Coventry is actually taking the lead apart from the Two Tone music, but also in education, because it set the standard, yeah, which the ministers saw because they funded this. Yeah, if you see the right is his speech in there, yeah, that is going to lead. And now all the accredited courses is right through the country. Yeah, the country was based on this. And this is history. This is, this is, this is funded. That's why the minister of the home office, yeah, this is the first thing to sell the courses, the goal is local authority schools, yeah, Coventry, yeah, to get involved in this, all the schools in Coventry. School in Coventry, to introduce the kit actually, because we're gonna go to run the session of music so that we get them into it. And that that time racism against nationalism was really, really, really thin. Hence this the birth of the Two Tone. And to sell this to the school and, yeah, in fact, as a result today, as we speak now, yeah, all schools, local, all local education, school in Coventry, yeah, has in them music, because we put that through. It was huge. Because now even Ellen Terry, you know the Ellen Terry Building [at Coventry University] came in to us because all other university bought into this, this education.

And not only that, because I sat on the board of BPI music industry, yeah, London, yeah, the commercial sector, a member of the BPI as a result from setting up, from setting up Glasshouse and being part of the board, I was on the board to try and introduce because at that time, I asked myself a question, What qualification as a producers got in the music industry? There is none quite you know, none at all. It's a matter of who you know and who you don't know. Yeah, that does you know that you're producing? I said, No, that's not on because, in a good thing, you must have qualification as a producer. So hence, part of the need for the training.

So at the commercial level, with BPI, I introduced training. Now the BPI got involved in that the commercial sector. And … that's how you got SSL, those SSL commercial training got involved to introduce training in the music industry. And you can see how many universities got music technology courses. This brought me in contact with [and I] even went to London, House of Commons, you know, brought me in contact with the highest thing, with the politicians, yeah, in order to secure the grant, you know, even just to start up these courses so all the … political people was very, very involved. I had to have meetings with them all over. It wasn't easy, you know, to sell this concept to our local authority in Coventry. And the minister recognized that this is a new beginning, and this will put Coventry back into demand. Because if you look at it now, Coventry can proudly say all the music technology courses that's been all around, like Sheffield, oh, Manchester, like our son that's actually gone through. How many kids have been through? That's where we are now. So it's not just this is the legacy: The Two Tone from the music to education. Not many people know this, and at the end of the day, I mean, I was lecturing, I think my department, I was lecturing, just not too long, I retired as a Lecturer in Coventry University after when I closed all these decided to have a rest. Yeah, he came back to university and did his MBA when he was 60. Yeah, after all this i had a rest, you know, I had to close everything down. You know, you did your MBA. I did my MBA, and they asked me, you know, be a lecture, to add value to the courses, which I did for seven years. Seven years, 6 or 7. Yeah, he retired at 71 right from Coventry University.

You know, so that's I was asking, Who should I talk to? And because … there's a story behind this that leads to this plaque and this plaque actually means quite a lot nationally as well. Just a follow up to follow up to the to the music, because when two tone music was involved, Madness, The Selecter, Beat and all that luck, you know, we were just opening the door.

Scott Leonard

Click play to listen to Scott Leonard talk about the impact of Musical Youth.

Audio Transcript

Hello, my name is Scott Leonard and today I am sharing Musical Youth, the Youth of Today cassette album. It's special to me because it was the first ever cassette album I was bought. I was bought it at the age of nine. So it's many moons ago in 1983. I come from a place called Bradford. My father bought me this cassette album of a band from Birmingham, whose lead singer was 11 and presented this to me and said, these lads from Birmingham are doing this.

What are you going to do with your life? Which is kind of cruel when I think about it, but also kind of encouraging and inspiring. And why do I think it's important to the evolving story of black British music and culture? Well, for me, it changed the way I thought about music. I was listening at the time to lots of different music, but this really presented reggae to me for the first time on my level by young people.

To me as a young person. And as I've grown older, I've obviously loved the music and loved the sound of this band. I went to see them last year and they're not the young musical youth that they once were, but they were still really relevant and they were still really capable of bringing a crowd together. The amazing past the Dutchie on the left hand side video was shot by Don Letts. I used to watch it on top of the pops and think it was really subversive. It was naughty and it was cheeky and they were sort of answering back to the judge.

So it kind of gave me this sense of, you can do this, you've got inspiration. They're right in front of you, not only from a musical capacity, but also from the videos that were being made and the attitude that they presented was just exciting. And it was kind of controversial, and it was very much anti-establishment. So it was a new sound that presented a new way of potentially doing things, and gave me a lot of inspiraLon as a nine year old boy in Bradford. Thanks musical youth.

Sherrie Edgar

Click play to listen to Sherrie Edgar talk about Black British music and Coventry’s nightlife.

Audio Transcript

Yeah, good. Okay. My name's Sherrie Edgar. I'm from Coventry, born in the early 80s, so I'm now in my mid 40s. I'm a visual artist, and arts and culture informs everything that I do. So that's why I've come to Black Sound today, February 2025 and it's been a brilliant event, coming together and talking about our stories and the history of music. And I think music informs everything that we do. It perforates every corner of our lives, and it reflects the environment and the people that are among us. And the way we do that is by switching on the radio, playing a record, putting a CD on, and it tells it's like the soundtrack to your life. So today, I've scoured around items that reflect my youth, my time in my teens and 20s, going out in Coventry, because Coventry nightlife was really vibrant, and that's why I love music. That's why music informs the work that I do as a visual artist. Because music brings people together, and it also brings those people together with those particular interests, so we can share those passions together and without those places to share those interests, then we become in our own silos and isolated and it, you know, it could cause many other mental health issues. But so, the items today I managed to find out up in my attic in amongst the photo albums was a photograph of Gigs. And this is when Gigs was just about getting on the scene. And as any of the musician artists, they tour up and down the country in clubs and venues to promote their new records, and this was in a club based in Coventry on Bishop street, near the post office, sorting office, and it just been renamed as a new club. It wasn't open very long because, unfortunately there was a stabbing, but and then it sadly got closed down. But Gigs was one of the first performances at this club, and he just smashed it with the record Talking the Hardest. And as we know, it's just become one of the biggest Grime songs to date.

Another record that, sorry, another photograph, shall I say I brought in is a picture of Beenie Man when again he came in the early 2000s I think he was maybe touring across the country, just reliving his his previous records, that he probably didn't have a track at the time, maybe just doing something with Janet Jackson around that time, and he was going around just touring the country. And what it was is that we had promoters in Coventry that allowed us to see artists, international artists. They would pay for these particular artists. And they were, they were driven through the yearn for Reggae, R&B, Hip Hop, those, those particular genres, from general music, from promoters asking for events, or, shall I say, organizing events in Coventry.

So the picture of Beenie Man, again, is in the same club, and he's just about to come out of the door, and I think he's on the mic. He's given the audience a little flavor to his unique signature sound of his voice, and he steps out and obviously causing a big, roaring commotion, like, you know, setting the crowd alight, and they're just firing up because he's coming out with his signature records that we all know, and so I brought that in, and it's telling at the time. You know, it's when events were still happening and artists were still performing at local events that were accessible, and you could just buy a ticket for probably 20 pounds, 17 pounds, and see an international, world class musician, artist, perform at arms length. And there was many across Coventry where that was happening, places like icon, the big super club that was capacity 2500 people. And you'd see, you know, the soul nights that were on Thursday and Sunday night across elamborough and diva, you know, that was Garage, R&B, Reggae was big. And the place that we would normally go would be West Indian Club in my youth, my informative years, it would be going to the West Indian Club. We'd go to a big dance, and then the night would continue right up until the early hours. We'd leave there and go to a blues and blues would start late, and the there was a particular house on Lockers Lane in Foleshill that would have the blues. And the music was really loud, really deep, deep bass sound. And it was bluesy, it was dark, and everyone was just rocking, and it was just a vibe, and it was just just brilliant, just it was mesmerizing. And it just, it captured your heart and your soul, and you were there in every mind, spirit and physical, physical way you were just, it just took you to another place. It was euphoria.

And so another artifact I brought in was my records, and that was that record. Case is one of four that I have at home full of CDs full of predominantly black music. It would be R & B, Hip Hop, R & B and Reggae Rock, Lovers Rock. And they scanned what would get the crowd going at the time was red wrap, that girl, that girl, Shelly Anne, and he would hear that again, a signature look. He'd be dressed very, very pale skin, black, Jamaican man in his red outfits, and it just again, it'd be a hype song that get everybody moving.

And then what I really wanted to bring in today was, in the early 2000s me and my son's Dad, we used to arrange clash nights at a venue at the back of the General Wharf in the early 2000s and when I was looking back on my emails today, I tried to scour even just one poster or one flyer, and managed to find one flyer. It was called RRR promotions, Roots Revival, Rude Boy Promotions, and we used to get sound systems come in and clash. And it would be the likes of Crusader, Alpha Sound, Quaker, the list goes on. I can't remember them all, but it would be Coventry would be the place where you'd hear sound systems all the time. And luckily, even to this day, we've got the West Indian Club, where there's, there's Foundation Fridays now where we do get, you know, a glimpse into these sound systems with Ozzie Holt and there's a few others from, from, but before my generation, before my time, and that there's no one plays like them. It, it's they, just they, they have a talent and a skill to be able to kind of put the records on that is that is right for that moment, for that audience, and the audience is never disappointed in it, the room is always on, they're kind of always alive. They're always lit. It’s alive and that's a very good skill to have. So yeah, that flyer was of my time when I was twinning my early 20s, and we would contact the likes of Goldfinger and Jah Tubby to perform for us. I still have the emails, and it would be literally writing to them by email that was, that was the form of contact or telephone calls.

But this, again, as it says in the question, you know, why we brought it, and why is it special? The problem is, as the story evolves, we're now looking back thinking we've lost a chunk of our time where we didn't document like we're documenting now. I just about got the photos I have. Who else has got photos of Beenie Man and Gigs in Coventry and other acts I have that's in my photo album, who has photos, possibly nobody, and who's got documents that that show those early, late 90s, early 2000 clash nights. There's nothing, because what, what would, how we would get to know would be free word of mouth. There was, we just, we just about had a mobile, you know, an SMS text message on the old Nokia or a poster. But blues wasn't promoted. Flashlights were probably just about advertised on a local radio station. You know, you've got Sting FM in the Midlands, but yeah, that I've brought it in because it's important to me, it's important to my generation, that this is what we used to do, and this is this. This talks about who we are. You know, I think it's now in in the mainstream. It's now in the big charts. But we fought, you know, nail and tooth, to try and have what we related to and what we found be accepted. It was, it was frowned upon. People didn't want new dressing with baggy jeans, big people didn't want new dressing with gold. Garage came. It came a little bit more acceptable to flaunt what you had, your diamonds, your gold, your Versace, Gucci. Oh, but now it's, it's you can't, you can't floss like that anymore. But in the mainstream, it's more accepted, and that culture is more accepted. You know, it's, it's not, it's not, you don't. It's not looked you're not look sideways if you've got cane rolls in your hair, or you've got big afros. So those elements of identity is far more accepted and long that may continue because it just expresses who we are. So that's music, and culture, and music allows us to be who we are. It forms our identity.

Brian Dobson

Click play to listen to Brian Dobson talk about So Far Sounds Coventry as a platform for up and coming artists

Audio Transcript

My name is Brian Dobson. I'm the curator of So Far Sounds in Coventry. The item I brought in for the archive is the first poster I produced for So Far Sounds coming to Coventry. So, So Far Sounds is a worldwide movement. It started in 2009; there are 400 cities that are So Far Sounds cities of which Coventry has been a So Far city since 20 April, 2022, and basically So Far Sounds gives up and coming artists a platform to perform in front of a dedicated, respectful audience. We have all genres of music, but we've especially had many black artists perform at So Far Sounds Coventry in different venues around the city, both black artists from Coventry from all over the country and from overseas. We've had artists from America, from Uganda and Ghana, performing here at So Far Coventry.

Click play to listen to Brian Dobson talk about the three albums he brought in and their impact.

Audio Transcript

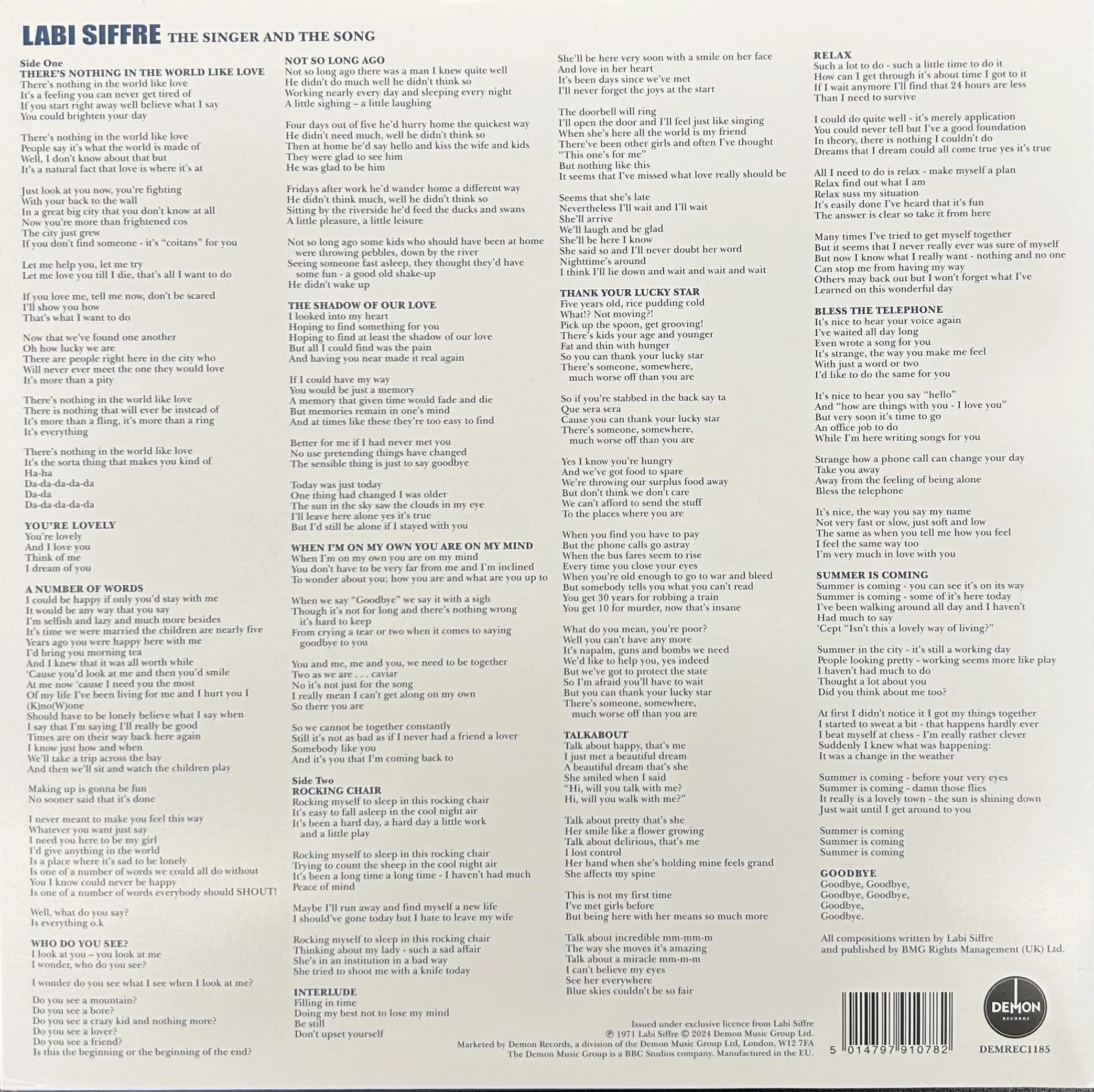

So my name is Brian Dobson. I've been living in Coventry for 35 years, and I'm older than that, by the way, but I've been 35 years in Coventry. I brought in three albums by black artists that are important to me.

The first one, the first thing to say is, when I was a young, 10 year old, back in the 60s, I didn't really think about genres of music. To me, music was music. I either loved the music or the music wasn't in particular interest to me. But I didn't think about Reggae or Blues or Soul or Rock or pop. It was just music to me. So the first artist that struck me, I brought the album in is Labi Siffre, and it's the singer and the song. So Labi Siffre is a British poet. He died just a couple of years ago, but he was a big influence on me in his songwriting, and he had a Folk feel, I guess, a Folk Pop feel, but with influences of sort of Soul and Blues as well.

The next album I brought in, is a more recent album, and that's Corinne Bailey Rae. And she brought out, Put Your Records On, was a big hit of hers, and I bought the album on the back of that. And the thing that struck me about Corinne Bailey Rae was she's very proud of where she came from, and she's from Leeds. So it wasn't a London based thing. I was living in Harrogate, near Leeds at the time. So that was a very important to me, that she was keen on her roots and her British black roots, I guess, in Leeds.

And the third album that I brought in is JP Cooper, and he's from Manchester. I bought his album on vinyl, Raised Under Grey Skies, and this came out of So Far Sounds. So I started following So Far Sounds many years ago when JP Cooper performed at the So Far Sounds so that's where I picked up on him, before he became a sort of bigger star, if you like. So it's always great to find new artists before they sort of break and become big. So JP Cooper, Raised Under Grey Skies. That's my third album.

Simon Phillips & Vijay Mistry

Click play to listen to Simon and Vijay talk about their past experience of black music

Audio Transcript

Simon:I'm Simon Phillips, DJ, broadcaster

Vijay:Vijay Mistry, Director at two funky arts

Interviewer:Lovely, definitely. So Simon, you're actually from Leicester as well, aren't you? I'm from Leicester as well. Whereabouts are you from,

Simon:Originally, born in Highfields, in the 70s, and then moved to Rushey Mead, Thurmaston in the in the mid 70s

Interviewer:Nice, nice, nice. Yeah. And also, you, you were on fresh FM, yes. And so, yeah, I'd like to know, like, what role did that play in the progression of your broadcasting career?

Simon: Fresh FM was everything, um, it allowed me to it allowed me to find my musical voice. It allowed me just crucial looking back now, I guess you know, training that I could be on, not could be I was literally on fresh FM. Overnight. I would get the key to open up the station at any given time, you know, to perfect my craft, there was no way was going to get onto any of the legal stations at that at that time, was a young black kid playing black music was unheard of, you know. So when pirate radio came along. It was just our way to to find our voice, to find our feet, you know.

Interviewer:Yeah, expression.

Simon:Absolutely so to play music, and then also to understand how radio worked, was everything. It was crucially important for me, and allowed me to find my voice. And then from that, you know, being on pirate radio at that time, and having records and having a platform that's like being one, probably like one of the first social media influencers put that into context of today. So that's what that did for me. It gave me a name, not only Just in Leicester. Yeah, anybody who could pick up the radio station within 75, 75 miles to where we were broadcasting to so it allowed me to play Derby, Nottingham, Leicester, Sheffield, Manchester. It was everything.

Interviewer:Yeah, and Birmingham,

Simon: One hundred percent, yeah. You know, it was everything.

InterviewerYeah. Wow. So a question for both of you, like, who are your favourite artists would you like to listen to? Who is someone who just helps you unwind after a long day

Simon:You can't, you can't that. That's like, who's your favourite family member?

Interviewer:Oh, yeah. Okay, that is a bit. I'll give you, like a couple

Vijay:I won’t say so much artist, but said, what kind of style and vibe, I grew up on eighties is kind of soul grooves and stuff. So if I'm chilling, if I'm jiving, if you know, that's my kind of vibe. But there's just too many good artists, but just good qualities. Whole music for me. The thing, yeah, he's that kind of vibe.

Interviewer:Yeah.

Interviewer:The amount of music we were cons- you know, just try even things to narrow it down, the amount of music that we've consumed forty years.

Simon:You guys are were there for, like, the rich, like artists, like who really put their everything into their music, not music now, where it's like two minutes long enough.

Simon:But I wouldn't, I wouldn't no, no, you've got that twisted. It's exactly the same. It's you just don't get to hear it. You get exposed. You get spoon fed. The algorithm nowadays is pushing the artist who is telling you that you must see there is a whole world out there that is, that exists. Personally, I think the music is probably better now than it was, because you've got 30 years of history. You've got all these artists to learn from, your Angie stones, your Betsy Wrights, your Aretha Franklins, your new artists who are coming through, who have sulked all of this in and then have a new story to tell with new technology, with better better musicians, better recording equipment. I personally think the music, the music now, feels like the reason why we were excited in the late 80s and early 90s.

Interview:Wow

Simon:That's that's my choice, but because you go through Spotify or Apple Music, yeah, you're guiding down this road of a priority of somebody else wants you to see. We had our own stories back in the day we could talk soUL, but his soul probably isn't the same as my soul but they come from the same well, but we drink different glasses of soul. You know.

Vijay:It's too fast

Interviewer:Um, okay.

Simon:Still trying to think about that question, because it's gonna get asked again, and I need to answer that. I think so.

Interviewer:Or, like a current artist now, like, who, someone who's upcoming.

Simon:I would say the moment, yeah, come Vijay, give me a second thing, because he listens to more music.

Vijay:Play. The problem is, like, Spotify I might listen to like a new playlist, and there's so much good music, so many good eyes, I can't remember who they were, because there's so many new ones in the old days. What we do, I do is about an album of an artist that I loved, and I listened to album 100 times, and like they said, I know who wrote, who produced it, whose feature. Now it's like, I'm in good music all the time. I ain't got clue what I seem to I'm not going back to stuff, just very rarely, where I find a god artist, and then I'll dig out their album, then listen to the album. But there's so much that can't remember anything. Honestly, it's really-

Simon: I’d say, one of what, sorry, one of the ones who was really redefined and defined where we are musically. Now, at the moment, it's probably Cleo Soul purely because she's not mainstream, she's not part of the big machine, but yet, she can set up the Royal Albert Hall, o that, again, proves that away from the mainstream, away from the big part of the industry, that our music can thrive and survive without that, which goes back to the initial DIY, things we were talking about earlier. So Cleo Soul for me is one of the leaders you've got Ezra collective long time coming, you know, they've been working away, and so we now that they're being able to, you know, be recognised for what they've been doing. It all depends on who has the torch and who wants to shine the spotlight, right? That's what it all boils down to, yeah, yeah, especially when it comes to black music, because there are so many acts out there that, and there are hundreds.

Vijay:I like SZA.

Interviewer:SZA.

Vijay:Yes, she's got good little sound.

Interviewer:Yeah

Simon:Again, long time coming. Yeah, It was H.E.R before that. You know that was.

Interviewer:Hmm H.E.R

Simon:Don't, get me started. Otherwise we're gonna be here all day.

Interviewer:We’ve got time

Simon:I always think about the Brits, because I've always been quite British, I believe that we've had the harder time because, you know, us following the American music. You know, I think we touched on that to early when Lloyd that we always have to be second best to the Americans. Whereas I've seen that evolution happen, where the Brits have finally been acknowledged for our own sound the way we are at the moment. Yes, it comes from an American branch, but we have a different story and a different way of making music, and how our music reverberates to our people here in the UK, yeah, which, which, to me, is the most important part. Don't get me wrong. I love the American stuff, but the Brits, it's always been about the me.

Vijay:There's a lot of good music for Britain, I think, in the olden days to get overlooked, because it's always about the importance-

Simon:It sound naff as well It sound awful that the street sold era. It was, it was naff. But we loved it because it was, it was, it was exactly great on the sound systems.

Vijay:You know, but even you had good, fun, loose ends, yeah.

Simon:Let's not get twisted. But the street sold stuff

Vijay:Yeah, Yeah, Yeah.

Simon:It was naff but we loved it. It was, it was ours.

Vijay:It was our sound.

Simon:It was ours. It was just had so much bass. The vocals weren’t tuned properly. They were singers were naff. But it was great. It was amazing. It was, you know, yes, great. You guys missed out on such a bright area.

Interviewer:We did, honestly.

Simon:But here's the thing, though, you can create it, but what this? But the music's not important to you guys, like it was to us, yeah, even now in our 50s, it's, I get, I get goosebumps just talking about it. It's almost like your tiktok or how important your social media is to you, that's what music was to us.

Interviewer:Yeah, Yeah.

Simon:That's the only way I can, I can equate it, you know,

Interviewer:Like, what was like your earliest memory of like music? Because I can tell, like, it's so like, deep in you like music, it's just everything, like, what was your first.

Vijay:For me, because I wasn't like, obviously, as a DJ, so it was probably a different world. But, yeah, just a consumer that just loved music. So I think from about, I don't know when I was about 15 - 16 up until then, I just listened to pop music. But about 15 - 16 I discovered all those groups, like Shallow on So Expanded all that song stuff. And they were just, I think when I listened to that music, it touches you like nothing else can. And then I just got so into it. And just by like, I was buying music, just for myself. He was DJing, but I was just buying, buying, you know, it's so hard to visit. You feel it, don't you? Yeah, you know. And you're just passionate about it, and that's why I think listening to music so much and being so involved in buying magazines and getting into it, he was almost inevitable that I'd make a career out of it, or a business. It was not what I was thinking when I was younger. But the more you kind of get into your 20s and you just live in it day and. Like, you know, I mean, yeah, so it, obviously, it turned into my business and my career. You know, 30 years later, I'm still doing same kind of stuff.

Interviewer :Wow. And where would you like to see your careers, like, in the next five years? still doing this, still being music lovers.

Vijay: Music lovers, 100% like, I say, I do this. I do all this stuff in music now because I run music venues and radio stations. So I'm doing, I'm still carrying out my passion, but through different ways. But it's kind of open now, because promoters are coming in, putting on events from Afrobeats to Jungle to R&B to Garage to whatever. So I'm kind of creating outlets. You know, we've got radio station DJs can come and play their music for the people. So for me, I'm not hands on actually doing stuff, but I'm creating opportunities for the music scene.

Interviewer:Yeah

Simon:That's, that's where the broadcaster and the DJ are two separate entities. Professionally, I'm a broadcaster. That's what I do for a living. I've taken what I learned from my journey doing specialist black music radio and then being able to translate that, you know, essentially, it's my nine to five broadcasting. But DJ that's that's a separate entity, but they do much, and they do play very important parts of each thing, because DJing fuels the radio, because I know how these records interpret and react in a club, so I can bring there and use that relatable experience to the radio. The radio then helps to fuel the DJ site, in part, but they're important. I mean, my mind sweat collection. I mean people are gonna laugh. And my family, I could call any one of my families now, my first two words were playing records.

Interviewer:Really? No, that’s just so beautiful.

Simon:As a two year old. Wow. I my auntie had a huge record collection, and my mum did too. My mum and my auntie were huge record collectors. I'm a benefit benefactor of what came before me, because my mom My mom, my auntie, used to buy records on a Saturday. They'd go into the market, come home, big batch, seven inch records that clean the house and play records Saturday morning. It's my uncle, a huge jazz collector. All my family were big record collectors, so in those days, it's very different. Now we had a weekends, what's called families. So there was none of this going out and doing whatever else we had Monday to Friday, your time, weekend family time, Sundays of Grandma's period. One thing that was always in all of our houses was records. So that we were I was exposed to records from as far back as I can remember. So for me, Records was the thing. And also, at the time, you got to think too socially, how different it was for black people out in on the streets of the UK. Yeah. So we were always safer together in our families, yeah. So house parties and music, music play a huge part of things going on.

Interviewer:And I feel like that's been a common theme. Like, even throughout this event, like the Maccabees, they literally came into the panel and they were talking about how their group actually kept them off the streets, like it was, it was a space for them to be safe and express themselves. And they were meeting at um, daddy sly's house, and it was like they were safe there. And that's so beautiful to me. I think that's what's lacking today.

Simon:Yeah, I mean, if you, you know, if you, if you've ever had the feeling of being chased down the street with a guy with a cricket bat with nails in it who will hit you with it, it's not a it's not a nice thought. It's not a nice feeling to feel knowing you can be attacked, or could be attacked, or in most cases, where it's at when you're right in the street. You know, people talk about racism nowadays. You guys don't actually know how good you got it. You don't. You know, the tables are turned. As a matter of fact, I feel that maybe the white people can feel a little bit more presence by the by the dominance of black people now in the country, you know me, I look at the films and stuff from the 70s, and it feels like a complete role reversal. This is why it irks me a little bit when people talk about racism, because unless you've known the journey of where all of this has come from, you can't sit there and now start barking about racism when you have the freedom to go wherever you want. Your music is wherever you want, your food is wherever you want. As a matter of fact, black culture, to the point now, has been assimilated more so than any culture anywhere in the world. Black Culture dominates and runs the world period, through the music, through fashion. Most of the sportsmen are black. Most of the musicians are black. Didn't mean so I think people really. Mean to tread that line carefully. Yeah, when they're talking about racism. And I say that purely because this is going now a whole different route man, this man was, but it's a conversation that we need to start to have, because people use that race card, I feel personally when they don't have the goods to deliver what they want. Because we have, we've just had a black president in the States, really, if America was racist, then how did that happen. You know what i mean? I do get that certain. Let me just stop there.

It's a whole different thing. But along with that, is, is the music and going, going back to the point initially, you know, in the 70s, music was It was everything to us. And I, I don't think that could the power of that could ever be really put across, how important it was and how it made my elders feel, you know, being strict Christians and growing up in that environment, they were strict, and they were coming home. And now, as an elder, I understand, you know, the what they had to face, and during a nine to five to then come home, and then to hear that crackle on a record, and then to see all of that go away, and to see these people become happy and joyful and celebrate during that time of difficulties.or me, that was a switch. Everything from that point that was it. I wanted that feeling, yeah, I want. That's what I wanted. I wanted people were going through sh*t. Excuse My French. I wanted them to feel that. And that's pretty much the feeling that I still chase to this day. It's why I do what I do, and it's it's never going to go away. It's that, it's that it's that powerful. It's not just about playing records. He did’nt should set the shop up just to sell records. There's, there's something within all of us who's into music, I think within you too as well. But I think with this new generation, you're so overwhelmed with so much that you don't find your voice. We found our voice easily because we had no choice. Yeah, it was either that or what we're gonna do what work in the factory. Do you know what i mean?

Interviewer:Yeah, yeah.

Simon:Music work in a factory because that was music wasn't even an option back then. It is now, you know, in hindsight, you can look at it and go, Oh, yeah, but you had that, and you had that, but no, but we were creating these things. It's only now we can sit here and go, Oh, you know what, yeah, we did that at the time we were because it was all new. It was out of necessity, it was out of hardship, out it was all out of lack because we didn't have it. You guys have everything. I keep saying, you guys can start a revolution tomorrow, you could gather hundreds of 1000s of people tomorrow and not even hand out a flyer. To get 20 people to come to a party. We had to go around the whole investor with flyers, which we had to make and handwrite ourselves and give out to people and stand in town for three four hours. And yet, they got a party tonight. I got a party tonight. You lot. Yeah.

Interviewer:Motive at mine

Simon:We're all happy about this. Let's protest. I took the toilet paper out the toilets. Yeah. Meet clock tower tomorrow, three o'clock, bam, bam, bam, bam, bam. And you guys got back. You guys knew the power that you had within all of this technology right now, you lot will be dangerous. Yeah, you lot would be just unstoppable. And I do worry sometimes that with all, with all the things that you do have, whether you guys are actually finding their own voice, of finding the passion that drives you along, and that's one thing I would ask you to consider yourself. Are you doing what you love? Are you doing what you love, or are you doing what you do just to do it, because there's a difference, and if you do what you love, you will be sat here in this chair in the next three years having this conversation, not going for a midlife crisis, wishing you'd have done it 25 years ago. So I can chat, man, but yes.

Interviewer:Thank you guys so much. This is amazing. Wow.

Lloyd Bradley

Click play to listen to Lloyd Bradley discusses the significance of a DVD titled "Champion Sound: The History of Coventry Sound Systems

Audio Transcript

My name is Lloyd Bradley. The item I bought in is a DVD of the film champion sound the history of Coventry sound systems. It's special to me because I'm a Londoner born and bred, and I had never heard of, never really had a Coventry before this. And I saw this film maybe 15 years ago, and it fascinated me, and it was a brilliant example of how sound system culture has affected all of the UK, not just London, but there was this thriving scene in Coventry from the early 70s, and it just made me realize how important it was to protect the legacy of these things, to to have a record of them. And I found the film really important because it was that it was guarding a heritage. So that's what it is. That's why it's special to me this, but it's part of the story. Again, as I said, because it takes care of heritages, they'll now forever be a record of sound system history and Coventry. I.